2255. This is a number I specifically remember as individual digits, read one by one – two two five five. Those are the digits of a number long ago owned by my current mobile service provider, a number from which I’d order ringtones and music, wallpapers and screensavers. And here we all are, with an unexpected coincidence. Namely, in 2022 and 2025, no less than four graphic novels based around Nikola Tesla were published – as you may have guessed, two per year. Two two five five. And, of course, the number cited here is in direct relation to cellphones, which in turn have a direct relation to Tesla.

Next June (roughly seven months from the date this article is published) will mark exactly 170 years since the birth of Serbia’s most well-known and well-regarded scientist and inventor. A man whose body of work had moved – and changed – the world in a million different ways. Born as a frail child in a religious, even priestly family, in what was then known as the Military Frontier of the Habsburg Monarchy, young Nikola would, due to unforeseen and unpredictable circumstances, travel across the Europe of his time and end up in the USA, where he would rub shoulders with some of the most prominent public figures, both in business and science as well as art and literature.

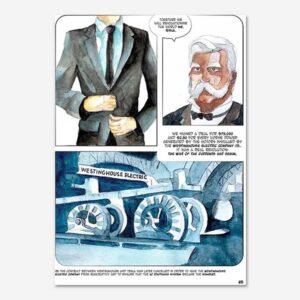

One detail that tends to be discussed quite frequently, even today, is the relationship between Tesla and the Italian scientist and inventor Guglielmo Marconi, mostly revolving around the disputes around radio patents (a brief reminder; Marconi won the Nobel prize for his work on wireless transmission, though early accomplishments in this field are attributed to Tesla). That being said, there’s a sense of poetic justice that an Italian comic book author, living and working in Belgrade, would craft a graphic novel about Nikola Tesla, his life from birth during a particularly stormy night to his final breath in a New York hotel room a little before receiving a visit from the agents of certain American secret services.

Said author of this graphic novel is Daniele Meucci, who used the watercolor technique to tell Tesla’s tale in no less than 15 chapters, By doing that—whoah, wait a minute. Wait just a minute! HOLD ON! Why is this article in English? The web portal it is originally published on is in Serbian, it is an aggregate of articles on culture and current events in Serbia and the region. Why would it be in English?!

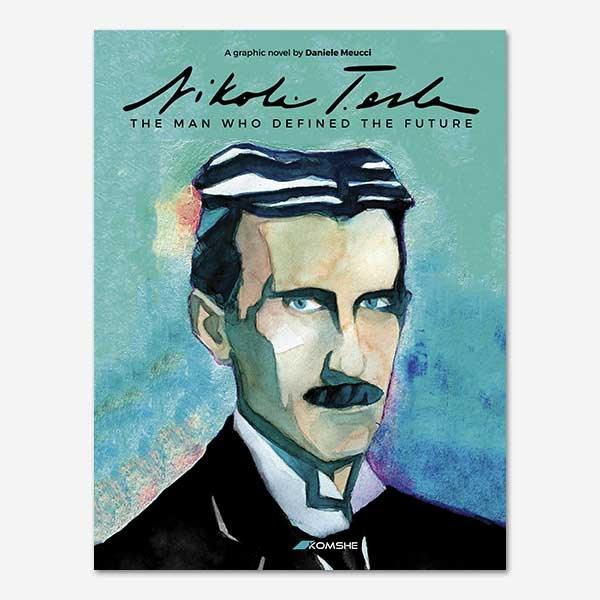

Well, dear reader, the answer is fairly simple, and it’s twofold. Firstly, there’s a nice stylistic element that matches this writer’s decision to write the article in English. Namely, in 2022, the graphic novel Nikola Tesla: The Man who Defined the Future, was published in both English and Serbian, thanks to a successful Kickstarter campaign. Therefore, I deem it appropriate that two separate reviews, in two different languages, are warranted.

But the other reason is somewhat more personal than the first, and hence slightly more important. Namely, Meucci, despite living in Belgrade, still struggles with his Serbian. Having kept in very sporadic touch with him for a few years now, I informed him of reviewing the graphic novel, and he was quite excited to give the review a read. So, Daniele, this is my gift to you – a review in English, different (apart from the first few paragraphs) to the one written in Serbian.

But we’re here to talk about Tesla. The two editions, published by a relative newcomer Komshe, have a few slight variations, but the main body of the story is exactly the same – same art, same colors, same story beats, same dialogues. The differences are mostly technical between the pair. For example, the Serbian edition has the title at the bottom of the front cover, in a big white font. The English edition has the title at the top, using Tesla’s signature as the first section of the graphic novel’s name. The English front cover is also somewhat cooler (as in “more cold”) than the Serbian one, featuring a blue tint across the background and some of the facial features of Tesla himself. The Komshe logo is also shifting, but also entirely missing on the back cover of the English edition.

Interestingly enough, it is the English edition that has more of Meucci’s biography listed on the French flaps/gatefold covers. The Serbian edition has one paragraph on the front flap and a brief description of the graphic novel on the back flap. However, the English edition features both of those on the back flap (with some added info and even web spaces where the author can be found online), while the front flap contains the blurbs from some of the industry’s most-respected professionals like Iztok Sitar, Dejan Nenadov, Aleksa Gajić and Davide Toffolo. Furthermore, the English edition has had a run of 2200 copies, 200 more than the Serbian edition.

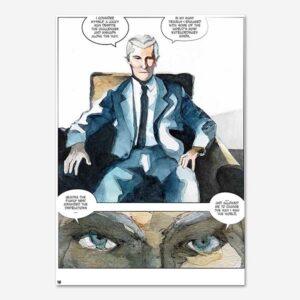

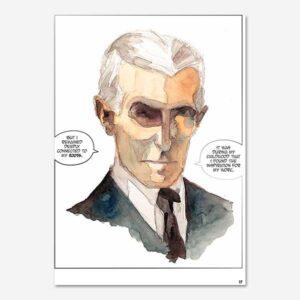

As stated in the Serbian version of this review, Meucci is a creative storyteller in more ways than one. Just the fact that he used watercolors alone would be enough to put him on the map, In a sense, he is similar to other masters of the field such as Blacksad’s Juanjo Guarnido or Meucci’s fellow Italian artist Stefano Turconi (or even the aforementioned Iztok Sitar in some of his works). But Meucci goes a step further. Look at the composition of his pages. Over 90% of them have curved corners, giving each page a rounded, soft look. But more importantly, he’s done something I’ve rarely seen in comics across the globe. Namely, when you look at his word and thought bubbles, nearly every single one of them “contains” a side that has merged with the edge of the panel it’s in. There’s a reason the term “contains” is in quotation marks – precisely that section that is supposed to be merging with the edge is missing. In other words, it provides an optical illusion for us and our eyes want to fill in the gap. In that sense, considering some massive missing sections, I daresay that “Nikola Tesla: The Man Who Defined the Future” might be the only graphic novel where every single panel is uniquely shaped. The only real discrepancy is the panels that have zero panel borders, so the text simply blends with the background, which also makes them unique simply based on the fact that they have no shapes.

Speaking of space, Meucci tends to use empty white backgrounds to his absolute advantage. Emphasis on certain objects, portraits, compositions and actions is palpable, and more often than not it’s these pages that take the reader’s attention the most.

As a storyteller, Meucci is fairly conventional, considering the story is based on a 1935 Liberty Magazine interview with Tesla. Therefore, we are actually listening to Tesla’s own words, his own retelling of his turbulent life, at the threshold of his final decade on this Earth. And a vivid biography like his naturally deserved a vivid storyteller like Meucci.

With that in mind, I can’t do much other than recommend this graphic novel, be it in Serbian or English. It is well worth your time, and it will make you a fan of Meucci’s work overnight. Don’t miss the opportunity and enjoy this lightning in the bottle…erm, on the comic book page.